Australia and the Stolen Generations

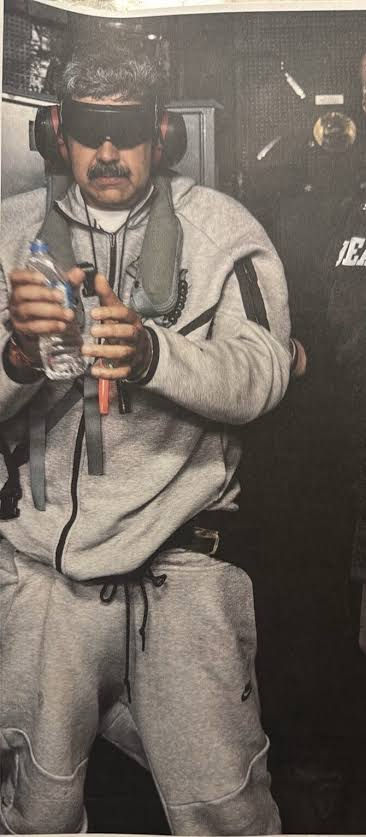

- Sebastian Palacios.

- Aug 9, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 13, 2022

Australia was colonized by the British in 1788 without other European governments protesting too much for being a territory that was too far away from the main commercial routes. With the independence of the United States in 1783 and a war that was coming with Spain and the Netherlands, the British Crown sought to replace lost colonies and have a safe place from which to attack naval bases of its enemies in the Philippines and Indonesia. To disguise these intentions, the initial official plan was to use this territory to send convicts from Great Britain who had been sentenced for minor crimes and thus solve the problem with the increasing prison saturation in the British Islands. The first ships arrived in 1788 trying to settle down in modern Sydney, and four years later the European population consisted approximately of 4000 men and 800 women, from which about 1000 were 'free people': the military, bureaucrats, merchants and landowners from the British Empire. Aboriginal Peoples had lived in Australia for 50,000 years and, as in North America, the tribes were organized into confederations without private property. By 1830, British settlements did not cover more than 100 km radius around Sydney, but the 'free' population was already much larger than the convicts. This sparked tensions between landlords and Indigenous peoples, culminating in massacres by the British after houses, crops, and livestock from the landlords were destroyed by armed native tribes. Unlike New Zealand, initially the British Crown did not sign peace and understanding treaties with the native peoples, but rather sought to fully conquer all the territory of Australia. It is estimated that up to 1928, about 1,700 landowners were killed in attacks on private property, while 20,000 Aboriginals were killed in retaliatory British massacres and intra-Indigenous conflicts that emerged during the displacement of a tribe to new lands. British-brought diseases caused the greatest demographic loss for native tribes. While the death rate from smallpox among Europeans was close to 1%, among Indigenous it was 60%, causing their population size to shrink from 50,000 to 2,000 individuals in South Australia between 1788 and 1853. To defuse tensions between landowners and Aboriginals, Australia's colonial governments created reserve systems where local tribes could live by their rules and traditions undisturbed by the expansion of the landlords. This came after several failed attempts by colonial governments to integrate them into European society, such as giving Aboriginal families land to farm, housing, and primary schools. All these offers were rejected as the Indigenous people preferred instead to continue living their nomadic lifestyle. The British were convinced that the Aboriginal population would disappear very soon due to its constant demographic decline. Anticipating this possible outcome, they launched a series of measures to 'rescue' mixed-race children with lighter skin color and integrate them into the European lifestyle. At the end of the 19th century, Australia enacted laws that gave police and public officials the power to remove any indigenous or mixed-race children from Indigenous reserves if they suspected family neglect, and place them under the care of religious or state-owned foster homes. At the same time, the European population was afraid that this mixed race would become more and more prevalent in Australian society and displace the white race. For this reason, in 1918 a federal law was passed by the Parliament that gave the Chief Protector of Indigenous Peoples, a high official of the federal government, 'total control over all Indigenous women regardless of their age, unless they were married to a substantially European man', and his approval was required for any marriage between an Indigenous woman and a non-Indigenous man. From the early twentieth century to the 1970s, the Australian state applied an aggressive policy of removing children from 'dysfunctional' families across all the country regardless of race, although this was done to a greater extent with Aboriginal families which are at the very bottom of the socio-economic strata in the Australian society. In 1915, a federal law allowed also the removal of indigenous children from their parents without having to present evidence of family negligence in court because the Officials considered that the judges 'could not know how these cases of family neglect really happened'. An estimated 100,000 Aboriginal and 250,000 white infants were removed from their families without respecting human rights until the 1980s. Most of the population saw this practice, at a time when abortion was not legal, as something positive for infants and even families themselves, and that these measures helped to 'improved society'. Academic studies show that Aboriginal infants removed from their families were three times more likely to have a police record for breaking the law, twice as likely to use illicit drugs, have more physical and mental illnesses, and underperform in school than those that were not removed from their indigenous communities. Civil organizations have struggled to obtain economic reparations from the state, and this group of removed infants has been called 'The Stolen Generations'. In 1997 the first actions began on the part of the government to apologize to the Aboriginal Peoples and deliver money as compensation to the affected families. Many politicians and officials have opposed being part of this process considering that current generations have no responsibility for acts committed by their ancestors, that infants were not 'stolen' but 'rescued' and that it is unfair to use the money of taxpayers to make transfers to survivors. Currently, the number of those survivors is almost 18,000 and each one will receive about 60,000 dollars in a lump sum. Nevertheless, since the Australian state has made an official apology and ended these practices, there is today a higher rate of Aboriginal people who have been removed from their families and placed under the care of Australian Social Services due to strong evidence, and a judicial decision, that infants are at real risk of suffering family violence. In 1960, there were about 2,000 Aboriginal infants under the guardianship of the state, and today the figure is 24,000, which represents 16% of all Aboriginal children under 18 years old in Australia and this proportion is 8 times higher than for infants of other races. In the first week of August, the Australian government announced that all Aboriginal survivors will receive this compensation, thus closing a wound that had racist connotations in the country, but the problems of inequality and marginalization will not be solved so any time soon.

Comments