Why Estonia became a model for digital governance?

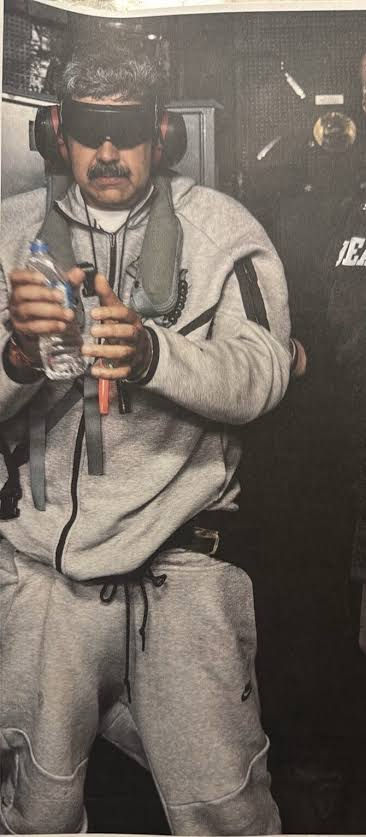

- Sebastian Palacios.

- Aug 25, 2022

- 4 min read

Estonia is a Baltic state with just 1.3 million inhabitants that gained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and has a language that, together with Finnish and Hungarian, is unintelligible from the rest of Indo-European ones, as it has Uralic roots. The country has a strategic location on the Baltic Sea and has been invaded by its Russian neighbor at least five times.

To secure full independence from its neighbor Russia, Estonia embarked on a series of reforms to modernize the economy with a digital approach, a symbol for leaving the Soviet past behind, and opening the society and economy towards the West, especially the Nordic countries, which had one of the strongest telecommunications sectors in the world. Because Estonia wished to join the European Union and NATO as quickly as possible, digital transformation was the best way to achieve the standards of low-corruption, transparency and democracy standards that both organizations require a country to have in order to be accepted as a new member.

When the Soviet planning system collapsed, so did export markets to the east, and companies needed to transform themselves into privately owned entities relying on Western products. The Estonian government established then technological transition by replacement as a guiding principle. This meant that public digital infrastructure should not use software that was older than 13 years; rather than buying large-scale solutions from established vendors to upgrade any Soviet infrastructure, government departments and agencies were encouraged to find open-source solutions.

Government ministries and their agencies had direct responsibility for their digital strategies, investments, and data architectures, so the organization was decentralized. Instead of having a unified database and information system, the focus was on secure interoperability between those systems through a national platform called "X-Road".

Estonia ranks consistently on the top 3 countries in the world on electronic governance, as one third of citizens vote online, 99% of government services are online, including procedures for setting up a business and filing taxes. In 2002, Estonia launched a high-tech national ID system by which physical ID cards were matched with digital signatures that Estonians use to do online banking, pay taxes, access their health care and even vote.

The benefits of this digitalization are clear; on average, companies and individuals in OECD countries spend respectively around 44 and 4 hours per year on tax declarations, while in Estonia the average is 18 minutes for companies and 3 for individuals. The rules are simple for individual entrepreneurs and investors based in Estonia:

• Corporate income tax is 20% and only applied to distributed profits, allowing companies to reinvest their profits tax-free. Companies are not taxed on the money they earn, but on the profits that are paid out as dividends.

• Contrary to the mainstream progressive tax system of most countries in the world, Estonia has the uniqueness of having a flat tax at 20% on individual income, and it is not applied in case of distributed dividends that have already been taxed with a corporate income tax.

• Property tax applies only to the value of land, rather than to the value of property or capital, and the system exempts 100% of almost all foreign profits earned by domestic corporations from Estonian taxation.

Estonia’s e-governance focuses on the individual and not the bureaucracy. One example of this is the “once only” principle, by which if one governmental agency already has key information about a citizen, then it is against the law for another agency to request the same information from the same citizen again.

The government is then responsible for this information being shared between agencies through the "X-Road" platform.

After 30 years since independence, Estonia has become a spot of innovative ideas like having flat income tax rates, free public transport for its citizens, internet access declared as a human right, and regulations that allow the testing of self-driving vehicles on its roads. This business-friendly approach has also led to the creation in 2014 of a state start-up, called e-Residency, which offers digital identity for non-residents that makes possible digital authentication and digital signing of documents without ever having been in the country. Currently, more than 20,000 businesses owned by foreigners from 120 countries have joined the program. Brexit has also provided a boost to this increase, as some 4,000 UK companies have set up in Estonia since the UK’s referendum on EU membership in 2016.

The results of e-Residency, digitalization and a friendly tax system have been very positive; since 1991, Estonia's GDP growth has been higher than in the rest of Baltic states. The number of private companies valued at more than $1 billion is the highest per capita in Europe, including well-known brands such as Skype, Bolt and Transferwise.

Moreover, Estonia’s taxation philosophy of simple and friendly rules allowed the country to collect more corporate tax per capita than most OECD countries, because companies have little incentive to cheat by hiding some income or holding back investments that help them to grow even more. In addition, government officials calculate that because of digitalization, Estonia is saving money equivalent to 2% of its GDP on corruption and bureaucracy. Transparency is indeed a central part of rule of law and economic growth, as it enhances directly a fair and dynamic competition between agents, and empowers different social groups within a society, and the case of Estonia is a clear example of it.

Nevertheless, the digital transformation has faced the challenges of receiving major cyberattacks from Russia, especially in 2007 and 2017, when many services were shut down for several days. Following this logic, after Estonia became part of NATO in 2004, a Cyber Defense Center of Excellence for the US-led alliance was set up in the capital Tallinn, and the government created a backup facility in Luxembourg where it stores copies of all of its data, in case Russia could launch major attacks.

National and international regulators have also warned that e-residency has made Estonia vulnerable to dirty money and sanctions evasions, and that being a digital society means to be prepared for constant cyber threats. No system will ever be perfect, but Estonia has shown that it is possible to put in place a series of policies that help to boost the development of any given country.

Comments